Superman! Superman! Superman!

The world is chanting "Superman!" in time with John Williams' epic guitar cover. A hopeful new DC Cinematic Universe is fully revealed in the first trailer for James Gunn's Superman film:

On July 11, 2025, James Gunn's DC Comics Superman, starring David Corensworth, will be released in theaters. Gunn is the screenwriter and director. At first, Gunn only intended to write the script for Superman and had no intention of directing the film.

James Gunn drew inspiration for the script from the All-Star Superman comic book. It is a 12-issue miniseries written by renowned graphic novelist Grant Morrison. In it, Superman tells Lois Lane his secrets and finds out he is going to die soon. Gunn has acknowledged that he has been a comic book fan for a long time.

Drawing inspiration from possibly the best Superman comic book in history? Awesome! So what can we expect from a film adaptation based only on the source material?

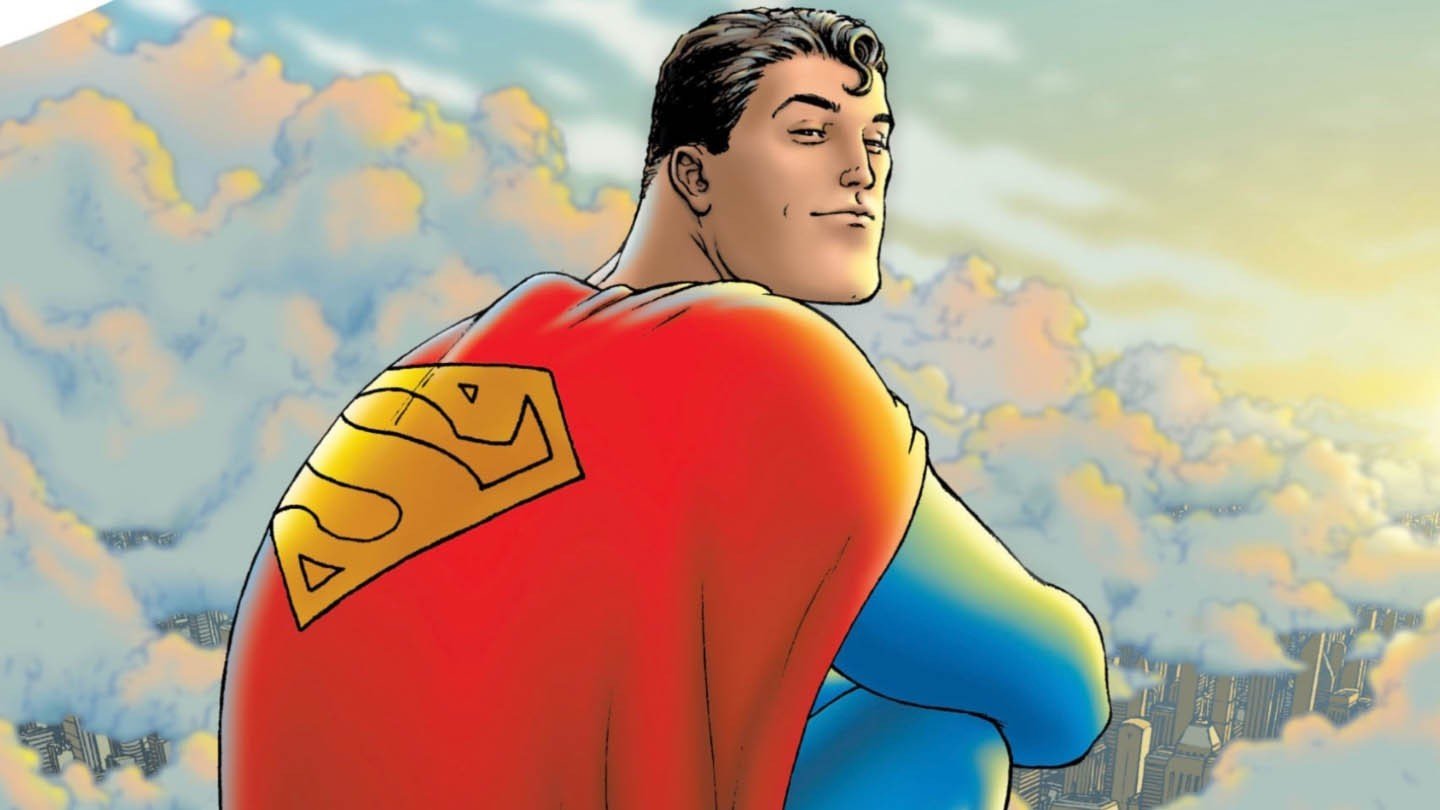

One of the greatest…

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

… Superman comic books of the twenty-first century, if not the best, is this one by Morrison and Quietly. For those who aren't interested in it, I'll try to pique their interest today. Especially in the dawn of the new DCU Era. For those who read this comic years ago and put it on the distant shelf, I also hope to revive their enthusiasm for it.

Warning: I don't consider the All-Star Superman storyline to be so important that I avoid discussing it for fear of "spoilerizing" it. What's exciting about this comic isn't that you don't know what to expect from the next page. I will try to avoid unnecessary retelling of the story, but the accompanying pictures and sample episodes are taken from all issues of the comic and may spoil some readers' enjoyment.

So, I have for you my reasons to love All-Star Superman.

Grant Morrison is a skilled and frugal storyteller

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

Morrison manages to reveal the series' plot, humanize the characters, and give Superman flying to the sun in the first issue while also reminding us of all the essential elements of the Superman mythos in a small number of pages. And that's sufficient justification to discuss.

The first page of the All-Star Superman series contains eight words and four illustrations that remind us—or reveal for the first time—everything we need to know about Superman's "origin." It's one of the greatest and shortest origin stories in contemporary comics. The image in our hearts consists of love, a new home, great hope, and faith in progress. All you really need are eight words and four images, but the writers will go into more detail, add depth, and build some concepts on top of it.

You can see how difficult it really is to write so lightly by comparing the comic to its film adaptation. So in one scene there is a blatant moment where, due to the "gluing" of two consecutive micro-episodes into one, Superman becomes the actual perpetrator of the deaths of several people.

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

Morrison's minimalism doesn't change throughout the series. In issue #10, Superman visits Lex Luthor in prison and tells him "Lex, I know there's good in you," who spits into the glass separating them and stares unblinkingly at the hero towering over him. Here the whole almost century-long confrontation between hero and villain fits into two or three frames.

Or here's number nine. The entire difference between Bar-El and Superman is expressed not in long speeches or illustrations of how differently they meet external threats. Not even in what other characters say about them. The entire difference is wrapped up in two panels in which Bar-El carelessly tosses a very heavy key to the Fortress of Solitude into a robot's hand - and Superman is instantly there to help his broken sidekick.

Morrison isn't the most succinct dialog writer, but when he's at his best (All-star is one example of this "peak"), he doesn't use any random words at all. According to him, he is especially proud of the "haiku about unified field theory" that a Quintum scientist said in the first issue and Lex Luthor said at the end of issue 12.

The door to the Silver Age of superheroes

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

The entire history of superhero comics in the last few decades has been a long-term effort to escape the Silver Age's shadow and the fallout from that endeavor. Carrying a chronology that spans many years is difficult, and carrying the "silver" portion of it is even more difficult.

In stories from the second half of the 1950s, editor Mort Weisinger's Superman faced the most ridiculous foes, got amazing alien pets, and found the most inexplicable ways to escape not just fantastic but downright ridiculous situations. How should we handle all of this?

The implication is that we all stand on the shoulders of giants, no matter how much we laugh at those giants in the face. And it's good to have an idea of what we're basing our lives off of, if not us, then certainly the authors we read. Just as it is not necessary in the twenty-first century to love and understand Dostoevsky (or Dickens), but it is still useful to know his legacy in order to trace the path that art has taken from "them" to "us".

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

But how do we look at the Silver Age? We can't go back to it. Even if we open old comic books, we won't read them with the same eyes that the children and adults of the past read them with. We are not accustomed to the manner used then to draw comics and write text for them. We will see flat plots, naive morals, ridiculous characters.

A museum is not a time capsule. It is not something you can look at for pleasure and then ignore. A time capsule is a message from the past to the future that lets you wake up, look back, and gain knowledge. The history of comics should not be avoided; rather, it should be used as a teaching tool. Morrison not only understands but also knows how to depict "what it was like to live at the dawn of the Age of Heroes."

For us, he and Quitely write a book that "translates" Silver Age comics into a language that we can comprehend. The Silver Age is the source of many of the tricks and techniques here, either directly or through deft imitation.

This comic is an inventively told good story

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

There's a quandary with Superman comics, and I've mentioned it above in another context. It's a problem most other heroes are spared from, and it forces the writers to be more resourceful than usual.

Superman doesn't need to fight.

Most superhero stories express any conflict: social, political, philosophical, through the physical confrontation of the heroes. This is necessary because the comic book is a visual art form, and inevitable because there are certain traditions in superheroics. But Superman can't do that, because we know he's going to win.

It's a difficult task, and even Morrison doesn't always pull it off perfectly: partly because he deliberately limits himself, doing in All-star only what could, at least theoretically, be done in a Silver Age comic book. But that's why most of the fights in the series end after the first punch, and why the most tense confrontations don't involve any hand-to-hand combat at all, like solving a great mystery. In the "new defenders of Earth" story, the test for Superman isn't whether he can defeat two Kryptonians: it's whether he can save them.

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

In the confrontation with Lex Luthor, only the villain wants the hero dead or helpless. The hero, on the other hand, wants—and in reading this is taken as seriously as it will now sound funny—to re-educate the villain. The only opponent that Superman simply beats is Solaris. Why? Right, because we already know from DC 1000000 that Solaris survived, re-educated, and started helping people, and Morrison can avoid wasting page space on telling us about it.

This is the meaning behind the claim that one of the greatest contemporary comic book authors is Grant Morrison. One slim magazine can contain all of the Superman stories' grandeur as well as their classic components and stunts. Superman fights Krull to save people, he competes with heroes to impress and prove his mettle, and he solves Atomhotep's riddle to save the person he loves the most.

It's a comic book about people

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

What does Superman think about when his life is at an end? Does he think about the feats he's accomplished, the incredible worlds he's traveled to? At least about the home planet he's never seen? No, he thinks of his friends, and the scene of Superman's farewell to his former life has both more space and more words for memories of them than it does for memories of miracles.

The same is true for the entire plot of All-star. Morrison doesn't have Superman in focus that often. We're more often looking at what Lois, Jimmy, Lex Luthor are doing and feeling. We see Superman scare, inspire, and motivate. We revisit episodic characters from the Daily Planet editorial team over and over again as they talk about or interact with Superman, even try to protect and save him. And what's the one thing from Superman's vast mythology that doesn't make it directly into the comic book that is mentioned verbally? His friendship with Batman.

Why do Superman stories focus so much on characters who aren't Superman? Because this way of telling the story directly and faithfully reflects our, as readers, relationship with Superman. We care little about what happens when this hero comes face to face with the villain: he's "super" and therefore will win. It doesn't matter so much what powers Superman has or how the villains' cars are designed. All Superman stories are stories about people. Superman's exploits only come to our attention when he saves people: individuals or all of humanity.

When it's not about Superman's friends and parents, though, we use the character as a jumping-off point. Silver Age comics asked this question a lot: what would have happened if Superman hadn't met Lois. Or had been raised by bad people. Or hadn't left Smallville. Or had magic.

A story about our relationship with the past and the future

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

In large part, All-star is a comic book about how the past affects the future and the future affects the past. The main commodity that superheroics supplies to its readers at four dollars a magazine is chronology. All or almost all of the stories we read continue the lives of characters we know. What happened in the comics last year sort of "really" happened. It's hard not to remember it or ignore it when we're obliged to consider the implications of what happened.

Morrison seeks to show that neither escape from the past, nor denial of it, nor slavish adherence to it can truly "conquer" the past. To stop being a prisoner of the past (and come on, we're talking about comics, not life, don't worry) you have to be able to learn from it, to build on its foundations.

This comic breaks down the boundaries between the narrative and the reader

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

I could not express the idea of this title less pathetically without using words like "metatextuality" and references to postmodernism. However, you know that where Morrison is mentioned, postmodernism is bound to come up.

The new Multiversity series that everyone is talking about now is the pinnacle (hopefully not the last) of Morrison's quest to create comics that speak directly to the reader. Not in the sense that the author's point of view on life's most important issues will be directly poured onto the pages, as is the case with the late Dave Sims, Frank Miller, and occasionally Alan Moore. No, Morrison wants us to be able to interact with the comic book characters as if they were real people, without ever forgetting for a second that we're holding in our hands a figment of someone else's imagination. Morrison doesn't play with the fourth wall, he reaches through it and grabs the reader by the scruff of the neck.

In All-star, the interaction with the reader begins with the cover of the first issue, where Superman turns around and looks at the reader. More than once or twice thereafter, the text addresses us—it's us, not himself or Clark, who Lois says "Let's go!" when she drinks Superman's potion, and it's Jimmy who addresses us when he says "Don't let him be seen like that!"

Image: ensigame.com

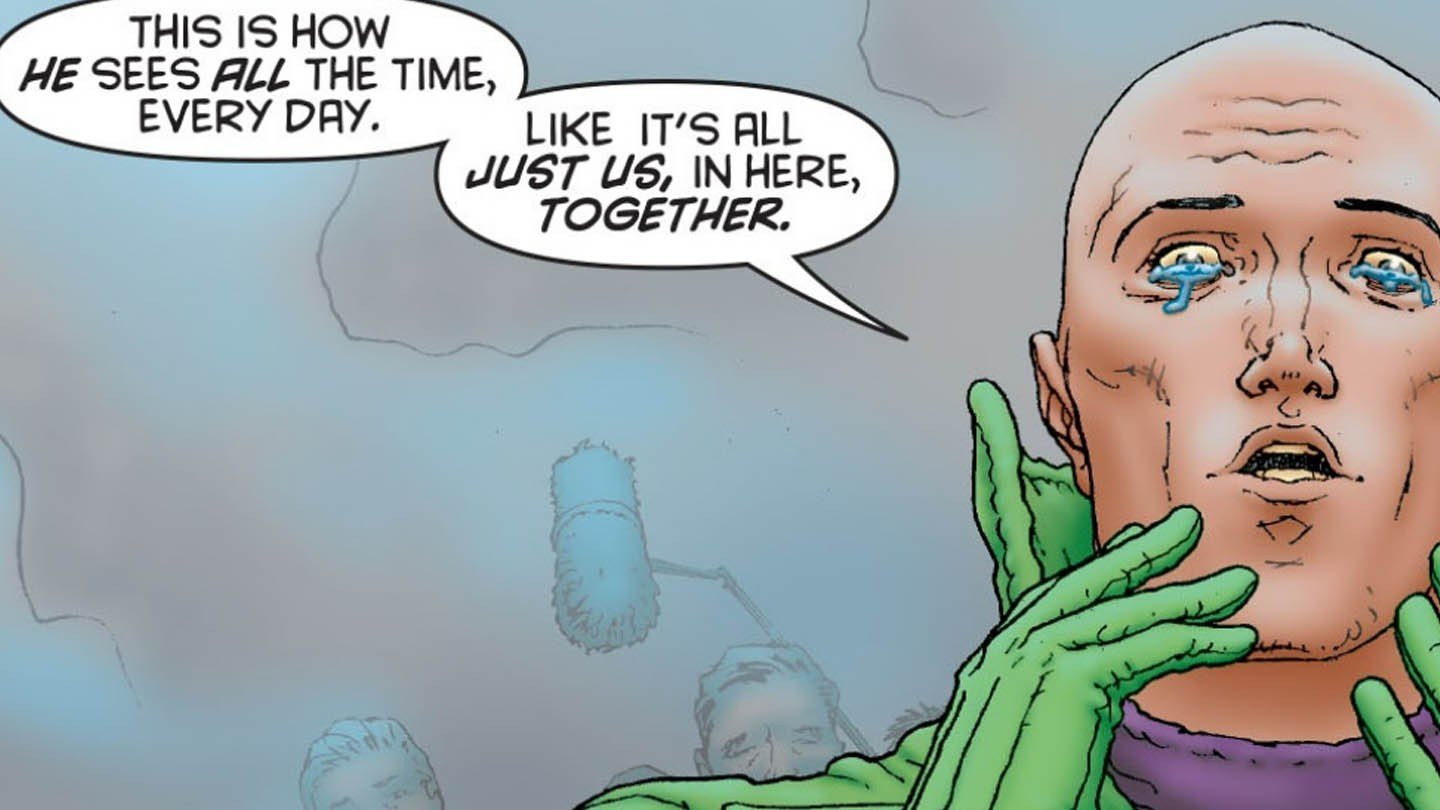

Image: ensigame.com

But the crescendo comes in the last issue when, with tears standing in his eyes, Lex Luthor looks up at us from the page and sees how the universe works. "We are all we have," but who is Lex talking about when he utters "So that's how he sees all the time, sees it every day?" Of Superman... or about the reader? And if you say about Superman, I'll just remind you that every issue (with few exceptions) has moments where we look at the world as if through Superman's eyes.

No, not just seeing other characters staring back at us from the page at point-blank range, but specifically finding ourselves in Superman's shoes, as he flies toward a goal or looks out over a changed Metropolis. To bring them into the article with proper context would require publishing entire pages, which we won't do. By issue twelve, the pupils looking at the page have become Superman's pupils more than once, and now Luthor, who sees the true structure of the universe, is looking into them.

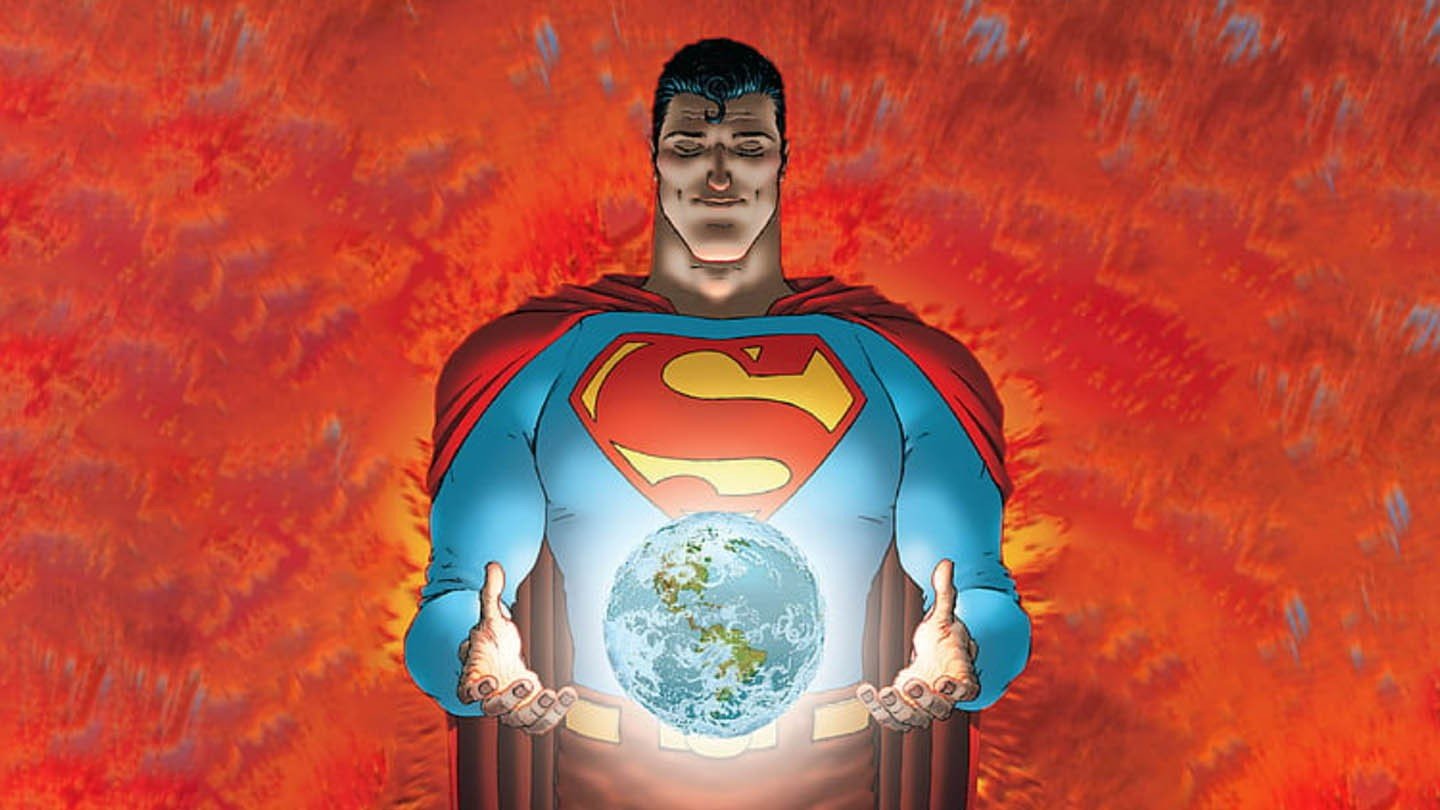

It's a story about boundless optimism

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

Have you ever wondered how we combine the individual elements of different stories about a character into a "canon" that we then consider more important than anything else not included? This process, done year after year by writers, editors, and fans, is for the most part more or less random. It's only when an author is faced with the task of forming a new canon that it becomes apparent what a chaos the hundreds of comics combined into one chronology really are.

Morrison, who at All-star was creating canon for a small but colorful finished series, could afford to reflect on the process itself and approach the matter philosophically. As a result, part of this Superman is the very idea of canon formation - in the third issue, Superman is visited by guests from the future who inform him (and us) that he will soon have twelve feats to accomplish.

And although the feats are not arranged symmetrically by twelve numbers, are not marked in the story, and in general some of them are difficult to notice without the author's guidance, we begin to look for these feats. And Superman doesn't, because he has more important and urgent things to do.

Image: ensigame.com

Image: ensigame.com

Superman's twelve feats are a canon that we form ourselves as we read. Just as the series itself becomes a "variant canon" of Superman as we read, whether we want it to or not. After All-star, "Superman According to Weisinger", "Superman According to Siegel/Schuster" or "Superman According to Byrne" is added to "Superman According to Morrison", even though it's not designed to tell new stories in the same "universe".

And these very feats - defeating Time, traveling to the "mirror" universe and back, creating life, defeating the sun itself and, incidentally, finding a cure for cancer inevitably lead us to the fact that Grant Morrison was not writing a simple story.

He was writing an epic.

And I believe that Gunn should reimagine it and make a bold statement this summer.

Main image: ensigame.com

Alexander "peter bjorn" Fadin

Alexander "peter bjorn" Fadin

1 comment